Exploring Collective and Personal Narratives with Groundswell Oral History Courses

Words by Allied Media Projects

In a moment where contemporary media tends to present hard facts, fast news, and personal opinion with equal fervor, oral history techniques can act as a way to center lived experiences as integral, trustworthy elements of history. Groundswell and its network of oral historians, activists, cultural workers, community organizers, and documentary artists are creating narratives that invoke social change in their respective communities.

Groundswell began in 2009 as a collaboration between Alisa Del Tufo and Sarah K. Loose, who was pursuing a master’s degree in oral history at Columbia University. After Del Tufo advised Loose on her thesis project, they sought to connect with other people who were organizing across a spectrum of social change initiatives. In 2013, they hosted a 3-day conference in upstate New York to continue these vital conversations.

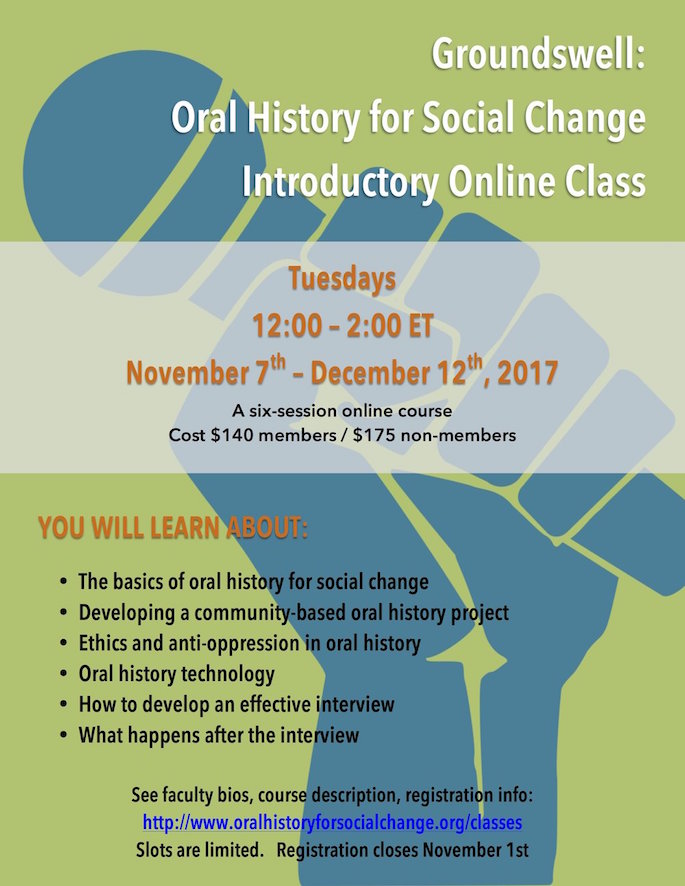

Groundswell has grown to include approximately 400 members who provide mutual support, training, and resources in the practice of grassroots oral history in order to build the creativity and power of social justice movements. Groundswell is offering two-hour online classes over a six-week period beginning November 7 and ending December 12. Instructors will share general oral history techniques suitable for participants ranging from novice to advanced experience.

To learn more about the forthcoming online class, we talked to Alisa Del Tufo, co-founder of Groundswell, as she considers the importance of oral history, personal narratives, and the bridge-building possibilities of collective organizing.

Who makes up the Groundswell team?

Alisa: We are from different parts of the US and have experience using oral history for some sort of social movement building or social change efforts. We are working to create a guide for how oral history can be used as a practice that centers the voice of people who have been marginalized and oppressed and what kind of values and strategies you would use to do that kind of work.

We are different, yet we act in some unified way, so we are really able to magnify what we do and bring a lot of power and resources to the work.

What is it like to work in a collaborative team?

Alisa: Each of us bring a different point of view, a different set of lived experiences and are people who come from different gender, racial, ethnic, faith, and age backgrounds to this work. We are different, yet we act in some unified way, so we are really able to magnify what we do and bring a lot of power and resources to the work.

What principles guide your work?

Alisa: We focus on action. Now, we have these stories and we have captured these voices, so we consider what we can do to make the world and our community a better place with this media.

Can you explain the importance of oral history in this particular moment?

Alisa: One thing that oral history is important for is really capturing the voice and experience of people who are older and may not be around for long. For example, people like Grace Lee Boggs. If people hadn’t documented her lived experience, we would be so much poorer for not only what we know right now, but it also has an impact for generations to come. The lived experience of different people needs to be woven together to address issues and I think that that’s where oral history really shines.

Something to really think about is that there are people in our own families and social networks who really have something that’s worth listening to and worth preserving.

How is oral history unique in relation to other forms of media?

Alisa: It’s a reflective, fluid, and improvisational process that is a very powerful experience for the interviewer and the interviewee. The beauty of oral history is that it is long form and unspecific. It’s not like journalism for example, as a contrast where someone who wants a very specific story about a very specific problem or issue kind of swoops into a community, ignores what some people say, and highlights too much of a degree what other people say which narrows the voices of people interviewed to specific quotes, often selected to reflect the biases of the journalist. Oral history is very focused on nuance and it’s a very patient form of working with people. It allows for difference of opinions.

Are there ways for people to become historians of their own experience?

Alisa: I started doing this work pre-digitalization and it’s a different world now that is easier, more fluid, and editable. Now, almost everybody has a recording device in their pocket that can be used to record sounds in the world or conversations between them and other people.

Something to really think about is that there are people in our own families and social networks who really have something that’s worth listening to and worth preserving.

There are also lots of free resources and books online by the Oral History Association.

What can people who take your class expect to learn?

Alisa: This class helps people who want to take this step and do a community narrative or oral history project. It gives people the building blocks that they need to actually put a project together. What really resonates with people is, at the end of the class, they can do the work that they want to do.

How has the course changed over time?

Alisa: Originally the class was an hour and a half and people said it wasn’t long enough, so we made it two hours. We’ve adjusted the content a little, but it seems like the basic elements of it have been satisfactory to people. I have added an ad-hoc session in the middle of the class, which is completely voluntary, so people can ask additional questions or get one-on-one attention.

Is the class beneficial for people who don’t have a community in mind?

Alisa: The course is intentionally general so that participants won’t feel like they’re out of their element if they didn’t have a project in mind.

What happens after the class?

Alisa: There’s a lot of communication afterwards. A lot of people that sign up for the class become Groundswell members, so there are other sharing and learning opportunities that they can take advantage of moving forward. There have been some interesting relationships and partnerships that have developed in the online class that have lasted over time.

Are there other ways for people to get involved if they can’t commit to the class?

Alisa: After this class is over, we’re going to be offering some mini classes that are focused on specific aspects of doing a community oral history project, including more intensive sessions on topics that come up in the class like conducting an oral history interview and crafting a community oral history project.

The deadline to register for the Groundswell class is November 1. Register now.